Book excerpt: ‘Misconceptions about Vietnam’

Hien Do Benoit Enseignante-chercheure

The recent 13th Congress of the Vietnamese Communist Party gave the ruling party the opportunity to congratulate itself on the country’s economic growth and its management of the Covid-19 pandemic. In “Misconceptions about Vietnam” (“Idées reçues sur le Viêt Nam”, available in French), Hiên Do Benoit looks at Vietnam’s society, culture and political and economic history, and provides us with the keys to understanding this state unlike any other. We present here the chapter that deals with the preconceived idea that the country is still fully communist today

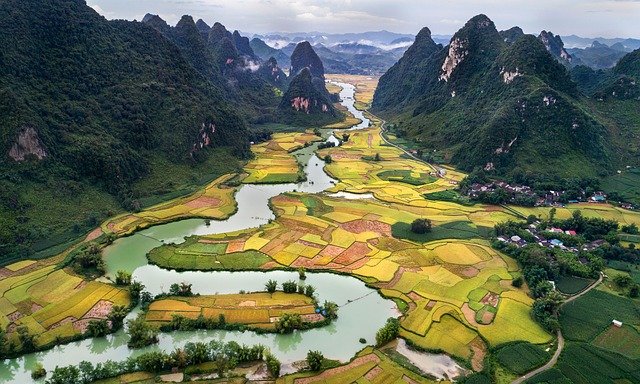

Viet Nam ©pixabay

First, communism per se should not be confused with the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP), effectively the only party in power in Vietnam, with a membership of some 5.2 million people in 2019, or around 5% of the population. In theory, communism is a social doctrine based on the abolition of individual private property – and the pooling of all means of production – seeking to replace a capitalist society with one based on equality and fraternity. In practice, within Vietnam’s one-party political system, communism as both doctrine and political behaviour is undergoing a complex reformulation. Today, not only is there is no longer any question of a class struggle but, rather, a “market economy with a socialist orientation” has officially replaced the centrally planned economy. Moreover, private property has never been so highly valued as today as a driving force in the process of national development. So, what is left of a communist heritage and how deeply entrenched is Vietnamese communism?

The Sixth Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam (VCP) in 1986 acknowledged the need for “reforms” both to redress a bankrupt economy and, also, to find for the country a way out of a hostile international environment. The latter was due to the conflict in Cambodia. The choice of Vietnam was astute, at least for that period. The desire to maintain the balance of power, to strengthen the political legitimacy of the regime, converged with the priority of promoting economic development. A regime cannot generally be politically legitimate without a healthy economic situation, but at the same time, any effort to promote economic development would prove futile if it was not accompanied by a stable political environment.

Thus, since the Sixth Congress, the Communist Party has been ready, not to really to question its control of the country, but, rather, to correct its mistakes in building socialism. This is precisely what its prime minister at the time, Vo Van Kiet, declared at the World Economic Forum in Davos in February 1990:

“Renovation does not mean a clean sweep of the past, nor does it mean abandoning socialism, but seeking to conceive more clearly a humane, perfected socialism.”

In practice this has meant encouraging political mobilisation around campaigns of criticism and self-criticism without tolerating pluralism. Reforms of all kinds remained strictly controlled by the Party. Vietnam’s doi moi (renewal) model is closer to Chinese practice than to that of Russian perestroika. For the VCP the essentials remained intact: Marxist-Leninism, democratic centralism, and a monolithic political system. The name “Socialist Republic” was retained, even though it was accepted that Soviet-style socialism had run its course and that the term socialism, itself, had to be redefined.

Thus, in Vietnam, being a “reformer” meant one was no less loyal to the Party, even if it was a Party that had to be renewed, modernised and democratised. It should be noted that, already in 1987, Nguyên Van Linh, then General Secretary of the VCP, had questioned the economic strategy of “jumping from the capitalist stage”, which was in his eyes “unrealistic and harmful”. There were already historical antecedents, namely the Luân cuong chinh tri (political theses) presented in October 1930 in Hong Kong by Trân Phu, the first general secretary of the Indochinese Communist Party. Doctrinal changes were also reinforced by the experience of a war economy.

After Vietnam’s reunification, the Fourth Plan in 1977 codified these changes and legitimised the conceptual foundations of Vietnamese socialist development. With the initial political theses, the party had given itself an economic orientation based on the Soviet model of linear “development by stages”. As the ethnohistorian Pierre-Richard Féray has argued, this model proposed, among other things, to “skip the stage of capitalist development” and to move without a transition from a “feudal” and “colonial” mode of production to a “socialist” mode of production. Furthermore, there was also a key idea established as a dogma in Asia by Mao Zedong: to make ideological considerations central in controlling the economy. The reforms since 1986 have attempted to reverse this trend.

Vietnamese international relations thinking, based on a vision of the world conceptualised through the sole ideological lens of opposing socialism and capitalism had long been sufficient to enable Vietnam’s leaders to obtain international aid in the form of support from “fraternal countries”. The collapse of the Soviet bloc in the late 1980s showed the need, not only for new partners, but also a reexamination of the criteria promulgated to obtain external support. In order to ensure, not only the development of Vietnam, but also the sustainability of the power they represented, the veterans of yesterday’s liberation wars, however, did not abandon the imperatives of “security and independence” of the country. They simply tried to take into account the new context in order to benefit from “favourable international conditions”. While there was general agreement that pragmatism was necessary, some leaders seemed to believe also that the failure of socialism was not due to a crisis of Marxist-Leninist doctrine, but, rather, to errors in “theoretical perceptions” and in the “application” of the doctrinal code.

The strategy chosen was formulated at the 10th Congress of the Communist Party (April 2006) in apparently clear terms: to continue and strengthen “reforms”, to perfect “the market economy along socialist lines” and to achieve “international economic integration”, since this global strategy is being implemented through a twofold action, both internally and externally. Nevertheless, this strategy is somewhat ambiguous and problematical, for it specifies as a primary condition for success inculcating a strong sense of national unity and a stable and secure political environment.

There are two major questions for the Communist Party of Vietnam in order to sustain its one-party rule. How should it manage its opening up to modernity and development opportunities, while preserving national sovereignty and identity? How can it take advantage of the “positive points” of capitalism in the pursuit of socialist construction? While reiterating Vietnam’s firm resolve not to see its sovereignty be diluted by globalisation, General Vo Nguyen Giap could not hide, in a conversation with former US secretary of defense Robert McNamara on November 9, 1995, in Hanoi, the perilous reality test Vietnam faced:

“Today, Vietnam is conducting its multilateral foreign policy. It has its own cultural and philosophical identities, but its level of technology and economic management still leaves much to be desired. We intend to benefit from the valuable knowledge and experience of all countries without jeopardising our culture, our spirit of independence and autonomy, and our Vietnamese character traits.”

In tracing the different stages of what he calls the “intercultural dialogue between Vietnam and the West”, the intellectual Huu Ngoc revealed in even more glaring terms what is at stake for the Vietnamese:

“In the cultural dialogue that we are conducting with the West, we are not in an equal position because of our level of economic development […], it is by no means easy for us to preserve our national identity.”

While socialism has not been called avoiding a into question, and remains an objective repeatedly confirmed in important documents of the CP (11th and 12th Congresses of the CP, in 2011 and 2016, respectively), a kind of economic pragmatism has been proposed. In rhetorical terms it seeks to make the current ideology more coherent, by injecting a strong dose of nationalism. It is indeed in relation to the outside world that Vietnamese nationalism today finds new impetus and new sources of inspiration. “A prosperous people”, a slogan that echoes the famous formula “get rich to enrich the country”, axiom proposed in Beijing by Deng Xiaoping in January 1992, has become a quasi-neologism for expressing patriotism in the country today.

The symbolic watershed can be found in the decisions taken at the 10th Congress of the Communist Party, which ratified the results of a heated debate that had been going on for years about the ability and right of every Party member, as a citizen, to be “prosperous”. At this congress is was decided that individual prosperity would contribute to collective prosperity, meaning that “capitalism,” which is contrary to the Party’s ethics and even its ideal had found respectability. In any case, members of the Communist Party can now – directly and officially – “undertake private business”, while preserving “the quality of Party membership and the essence of the Party”.

Today a comprehensive concept of security centred on this economic pivot, national unity, a collectivist sense of the nation, abetted by a reinforced role for the State and the Party, remain the key means for blocking what the political elite calls “hostile forces” from endangering socialism. In February 2007, quoting Ho Chi Minh’s words on the anniversary of the founding of the CP, General Secretary Nông Duc Manh did not hesitate to condemn individualism, which, by causing the loss of national unity, was indeed “harmful to the interests of the revolution and the people”.

According to Huu Ngoc, in Vietnam, the community spirit, which is contrary to Western individualism, is “understood in the sense of a national spirit, of love of the fatherland”. For the strategist Vo Nguyên Giap:

“Solidarity, the great spirit of unity, characteristic of Vietnamese culture, has given the Nation all its intense vitality.”

However, in this country where economic results are attributed to so-called Asian values – such as diligence, a sense of community, family stability, etc – some Western values are recognised as both universal and also considered necessary. During an international seminar on “Asian values and Vietnamese development in a comparative perspective”, held in March 1999 in Ha Noi, Vietnam’s blended approach was particularly praised for its ability to maintain a certain stability in the face of “international and national economic and social upheavals”. It was claimed that this was due, not only “to the partial maintenance of traditional values”, but also “to adopting certain Western values [such as] well-understood individual rights, democracy, gender equality, etc.”.

Translated from the original French by David Camroux.![]()

Hien Do Benoit, Enseignante-chercheure, Conservatoire national des arts et métiers (CNAM)

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.